Japanese Sake

Sake is more than just rice wine; it’s a traditional drink older than Japan itself.

In this episode, we're traveling to Hyogo, a prefecture known for its premium sake, to learn about how it's made and why it's so special.

We’ll talk to a fourth-generation Toji who's preserving tradition while doing things his own way. Plus, the owner of my favorite sake bar in Yokohama, who spends his day pouring bottles for locals.

By the end of this episode, you’ll be able to navigate this complex category and order like a pro. Plus, you’ll have some fun facts to impress your friends with!

Japanese Sake

Listen to this episode to hear all about:

- Why sake is more than just "rice wine"

- How the history of sake is actually the history of early Japan

- Inside the brewing process at a traditional brewery

- Exactly how to order sake at a restaurant and impress all your friends!

Meet me for a drink?

Get new episodes delivered straight to your inbox, plus stories from behind the scenes.

Sent weekly. Unsubscribe anytime.

© Between Drinks 2026

More from this episode

Transcript

Welcome to Between Drinks, a podcast where we travel the world one drink at a time.

I’m your host, Caro Griffin, a mezcal sommelier, traveling bartender, and all-around drinks nerd.

In each episode, I’ll take you somewhere new to dive into a local drink with a story to tell. We’ll talk about its history and how it’s made, but also its connection to the place and the people that make it what it is.

There’s a great story behind every great drink, and I can’t wait to share them with you.

Episode Intro (00:30)

I’m not gonna lie: I used to think sake was boring.

I respected it as something that’s been around a long time and is an important part of a culture. I ordered it at Japanese restaurants because that’s the thing to do, and even enjoyed it. But it’s not a drink that I found particularly exciting.

What changed that for me is what always changes it for me—I had a… wait, what? moment.

That moment was learning that sake was first made by young Japanese women chewing rice and spitting it out into a common container. 👀

The enzymes in their spit broke down the rice starches into sugars, which could then be converted into alcohol by naturally occurring yeasts…. Let’s go ahead and file this under “Another wild thing humans have done in the name of making alcohol,” umk?

Thankfully, things have gotten a bit more hygienic and systematic since then. But production is still rooted in tradition and craft, and all the things I love in a good drink.

As I’ve tried more sake, I’ve also realized how large the category is, how much the flavor can vary across styles, and how instrumental sake was to not only the history of other drinks in Japan, but the country itself… and it’s just really cool!!

But it’s also a complex category with lots of categories and subcategories… all of which are in Japanese, which can make it hard for foreigners like me to navigate without a cheatsheet.

So, let’s consider this episode my attempt at:

- Showing you what makes sake so cool and why you should care about it,

- And also, giving you that little cheatsheet.

This is the first episode in a series about great drinks coming out of Japan. And if there’s ever a country that deserves a whole season dedicated to its craft drinks… It’s the country that defines what it means to call something craft.

I spent nearly two months traveling across Japan for this episode and the rest of the season. It was my third trip to Japan, and it really solidified it as my home-away-from-home, so I hope you enjoy going on this little journey as much as I did.

Introduction to Akashi (02:25)

When I hopped on the train to visit the Akashi Brewery just outside of Kobe, I was only expecting to see the process. But when I got there, I was quickly handed a hairnet and hurried into the heart of the brewery. They didn’t want me to miss my chance to quote-unquote help.

You see, Akashi only produces one batch of sake per day… and I was running late! Eeek!

I hate being late at the best of times, but in Japan? Cue that gnawing feeling in my stomach, and a not-insignificant amount of sweat on my hairline from… let’s call it a brisk walk from the train.

The Akashi Brewsery is located in a city called, well, Akashi.

- It’s right outside of Kobe, in western Japan.

- It’s in the Hyogo prefecture, which makes more sake than anywhere else in the country.

- This is because it’s home to the best rice, the best water, and so, definitely some of the best sake.

People in this area have been making sake for hundreds of years, and the Akashi Brewery itself has been around since 1856.

They craft artisanal sake in small batches, utilizing traditional equipment and their own hands.

Every batch is made by just a couple of guys… and now there’s one batch out there made by three guys and me! Because like I said, they let me quote-unquote help, which was such a cool, hopefully not once-in-a-lifetime experience.

We’ll talk more exactly how sake is made in a bit, but for now, a fun tidbit I learned: handling sake rice makes your hands really soft!

Mine felt so nice just after one morning spent brewing. I can’t imagine how soft those guys’ hands are on the regular.

Yonezawa-san: There are many types of sake we have, but we are a craft sake brewery. Now we are making the sake with only three persons, and it's always that they are small batches... It's always that we try to make is a better product.

My team is… they have a good experience and knowledge, and we are very important in the teamwork. And we keep the traditional style. And one side is revolution, we spend a long time. If it’s always the same, it's not growing up. It's because the customer is growing up, is making knowledge. And the same is we are more, is better quality, is increasing the quality.

I try to try every day.

That was Yonezawa-san, the President of Akashi and its Toji, or head brewer.

He’s a fourth-generation sake brewer, so he grew up drinking sake, making sake, and has seen the industry change a lot over the years. He knows and respects the traditions, but isn’t afraid to try something new.

In fact, that’s what I love about Akashi in general. They are a great example of the “rooted in tradition, but unafraid to innovate” model.

They still make sake the old-fashioned way, but they’ve also expanded the brewery into a fully functional distillery that also makes gin, whisky, and liqueurs.

All of which I got to taste!

(Yes, there was a spit cup… No, I didn’t use it probably as much as I should have.)

Introduction to Sake (05:48)

Sake is often described as a “rice wine,” but it’s actually more of a rice beer… and yet it’s neither one of those things.

Wine is made by fermenting fruit (like grapes), which has enough sugar that yeast will convert those sugars to alcohol without much intervention.

Beer, meanwhile, is made by fermenting grains like barley or wheat. These cereals don’t have much sugar, so you first have to convert their starches into sugars.

This is how sake is made, too. Except that both steps (conversion and fermentation) happen simultaneously, thanks to a little mold called koji…. Which is the same thing that gives soy sauce and miso paste their unique umami flavor, by the way.

This unique production process, where both conversion and fermentation happen at the same time, is super unique. It’s part of why sake has its own category, rather than being lumped into the larger beer or wine categories.

Sake also distinguishes itself in a few other ways:

- For one, it has a higher alcohol content. Beer and wine clock in at about 5 and 12 percent, respectively, whereas sake is usually between 15-20%. So, generally twice as much.

- It also has its own serving methods. Just like how beer has mugs, and wine has specific glasses, sake has its own cups, carafes, and even little wooden boxes. It can also be served cold, at room temp, or even warm!

- Lastly, it has a unique flavor profile. You wouldn’t compare the taste of beer and wine to each other - they’re too different - and you can’t really compare sake to either of them either.

So, my main point is this: Yes, sake is technically “rice wine”... but it’s also so much more than that.

Caro: So is the rice from around here?

Yonezawa-san: Yes. Because we are a craft company, locality is very important. It's a Hyogo prefecture, we are—all of them, it's coming from Hyogo prefecture… farmers, yes.

Caro: So, have you been working with some of those farmers for a long time?

Yonezawa-san: Ah… a long time ago, I came back about 30 years ago, it's coming from the farm, it's winter season. They are making sake with me, and for half a year, they are working at Akashi sake brewery. And summer time, they went back to home, and planting the rice, and after feeding, it's coming back to our sake brewery, and making the sake.

Caro: That's so cool.

Yonezawa-san: Yeah, yeah, yeah, a good system. But now, it's six months, joining… to making sake. Because it's six months, it's a… they have a wife, stay at the local. Six months, only husband is coming.

Caro: It's like a part-time husband.

Yonezawa-san: Yeah, six months, right? They come back, and the wife is gone. [Both laugh]

Caro: Aw, okay. So maybe not a great system in that way.

Yonezawa-san: Now the culture has changed. My team is... all of the year, is a normal employee. They are studying the sake brewing and making the sake.

Japanese History (09:13)

Sake can be made anywhere, but it’s inextricably linked to Japan, where people have been making sake for almost 3,000 years.

It was the first alcoholic beverage in the country and, to me, the way it’s produced and served really represents not only the early years of the area’s history but also parts of its culture that have carried through to today.

Originally, only the government could brew sake, and only the upper class could drink it. It was closely tied to religious ceremonies and offerings at big, significant events like weddings, funerals, New Year’s, things like that.

Sake was more than just a drink. It was something sacred. It served as a bridge between the living and their ancestors, and was commonly used as an offering at shrines and temples.

Over time, this association helped shift brewing to the monks, who helped refine the production process. (Fun fact: These monks even created a rough pasteurization process before Louis Pasteur patented his!)

From there, brewing became a trade skill and eventually, a whole industry. This was between the 1600s and 1800s, and it was really when sake became the drink we know today.

- A lot of brewers set up shop in Hyogo because of its great rice and water, turning it into a capital of sorts for premium sake.

- Modern methods of production and pasteurization also improved the quality,

- And it’s when polishing the rice and adding neutral alcohol really became a thing, and those two steps play a big role in how sake is categorized today.

This was the first chapter of sake’s history, if you will.

Miho: So, you can now look at the label and you can identify what this means.

Caro: Yeah... okay. Junmai - no alcohol. G is 50% polish. Genshu is no water added.

Miho: Yeah, exactly.

Caro: Okay. So, no alcohol, no water, at least 50%. So, this one is even more premium then?

Miho: Yes... in terms of pricing, yes. So, all of them in the premium range sector depend on what part of the rice is used. So we call this premium, but in terms of price premium-ness, this is the most.

Caro: I think something I'm learning is that… the polishing doesn't necessarily mean that it's like better. It just means that it’s–

Miho: It’s style. Yeah, exactly.

Caro: … It just means that it's a different style. Yeah, it's a different style and it is more expensive because it takes more work. [Cross-talk]

Miho: Yeah, exactly. And then take a longer fermentation, longer process, more rice you have to use. So all of them are premium. So it depends… It's nothing better. It's nothing like a Junmai Daiginjo is always better. It's a style of the taste profile.

Caro: Exactly. Yeah, I think that's so…

Miho: So the reason why we have different styling varieties that we are setting also overseas is that we want to kind of showcase the taste profile. Different little bit of the production method can make a different taste.

How It’s Made (12:14)

That was Miho Komatsu, the Global Brand Manager at Akashi, explaining some of the categories of sake during my tasting at the brewery.

There are many different styles of sake, and a lot of them are based on how it’s made. But before we get too far into that, I want to clarify one important thing…

Sake is technically the Japanese word for all alcohol. Nihonshu is the local word for what we foreigners know to be sake.

For my own ease, and because this is an English-speaking podcast, I’m going to keep using sake… but take note. If you go to Japan and order sake, they will know what you mean, but technically, nihonshu is the more correct word.

So, now on to how sake, or nihonshu, is made!

Rice Polishing (12:55)

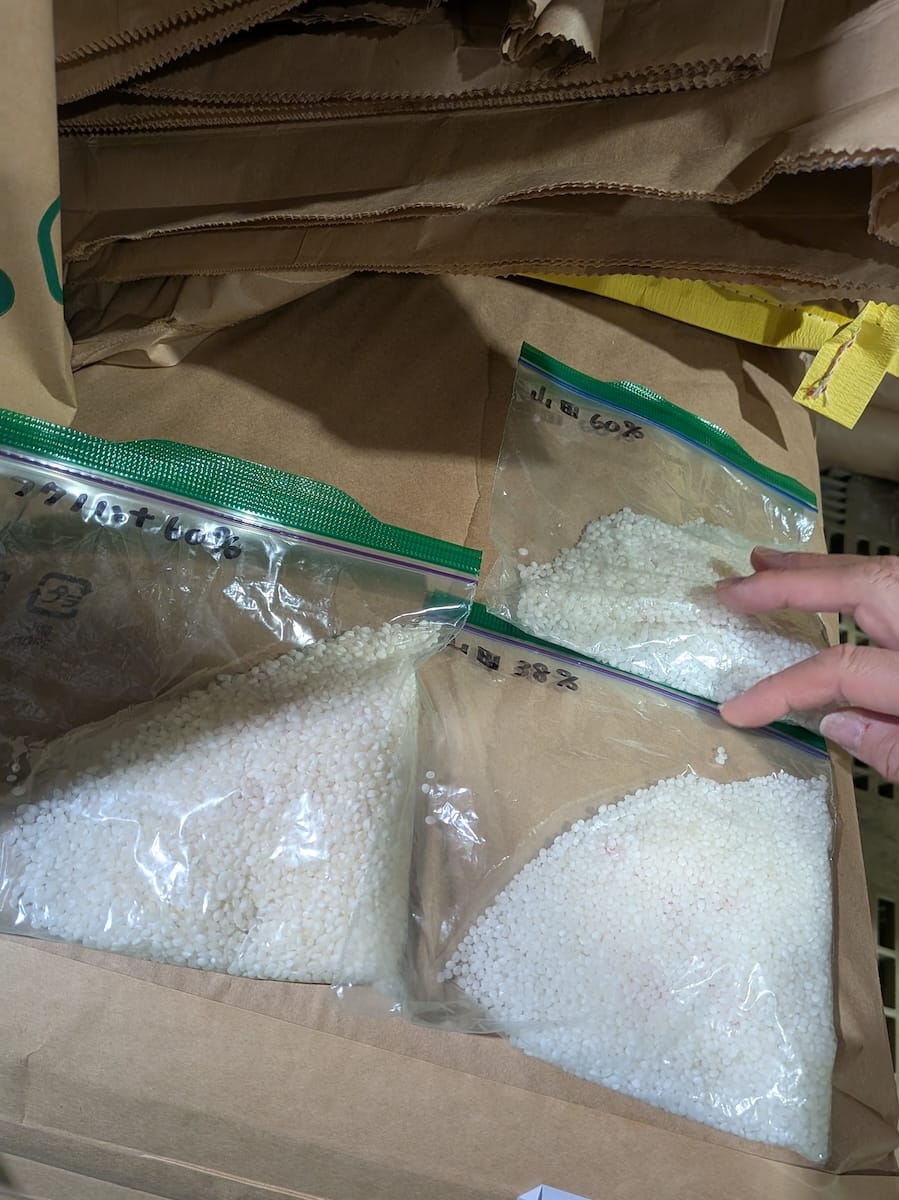

The first step of sake production is arguably the most influential. It’s called rice polishing.

This is where the rice is polished to remove the outer layers of the rice grain.

This is done for two reasons:

- The outer layer contains proteins, fats, and minerals that can cause bitter or sour flavors so removing them makes the sake taste better later.

- Polishing off the outer layers also exposes the starchy center of the rice grain. These starches are necessary for fermentation. Without them, there’s no making alcohol!

Sake rice is polished to various levels, and there’s often a misconception that the more polished the rice is, the better or more “premium” the sake is. But that’s not exactly true.

Sake made from more polished rice is more expensive, but it’s not necessarily better.

It costs more to buy because it costs more to make. If you polish away half of your rice, after all, you’re only going to have half as much sake when you’re done. And so, it takes more time and more rice to make - hence the higher price point.

Affordable sake is usually polished to 70 or 80%, which means 20-30% of the rice has been removed. This is often referred to as “table sake.”

The sake we think of as “premium sake” might be polished up to 50 or 60%, and so that means more than half of the rice could be removed.

The more the rice is polished, the more delicate the flavors tend to be, so, in large part, it’s about your preference as much as your budget.

Brian: Yeah, when I first moved here, there was a brewer that polished it to 1%, which means they removed 99% of that rice grain had just disappeared, and only like a little speck of dust remained.

They did it for public relations reasons. It's not practical, of course. So it's a question I've, you know, I've posed to several brewers as well. Most of them give you the same answer. They say, once you go beyond 30% or maybe even like 25%—25 is pretty extreme.

So again, this is the percentage that remains of the rice. So, after the polishing process. So, let's say if it's 30%, you just polished away 70% of that rice grain. So, they say, after that, you don't gain anything after that. You're really just kind of wasting at that point.

Caro: Yeah, yeah, totally. It's like, you know, maybe an interesting exercise or experiment to do, kind of the 1%, 10%. But at that point, it's like, yeah, it's hard to think of it as like, are we just wasting rice? [Laughs]

Brian: Yeah, there is a trend, the current trend right now, it started maybe about two or three years ago, is that they're doing minimum rice polishing. So, there's a lot of brewers… they might even put it on the front label with a big number 90, which indicates that 90% of the rice remains. They only polished off 10% of the rice. So it's a way to showcase the skill of the brewer. So, usually to make a sake that has a very pleasant taste, it's… and you only polish it to 90 % not easy to do. It really like I said it kind of showcases the skill of the brewer.

Caro: Yeah, I kind of like that, know, maybe a little bit… backlash is too strong a word, but like a little bit of a pushback of like, we don't have to, you know, just keep polishing off rice. Let's try to be… that other end of the spectrum of like, let's be creative. Let's experiment. Let's show off our skills and see, you know, what can we do with 90%? I don't think I've ever had anything with that low of a polish rate so I'll have to keep an eye out.

Brian (19:4): Yeah. They're probably sakes that would never pair with like a sushi or sashimi because they will have much bolder flavors.

Intro to Brian (16:30)

That was my friend Brian Hutto, an American expat living in Yokohama, a city that’s so close to Tokyo it’s practically still Tokyo.

Brian owns a great standing sake bar there, Craft Sake Shoten, which I was lucky enough to stumble across on my last trip. We’ll talk more about that later, but for now, just know that I invited Brian to chat with me for this episode because I think he has an interesting perspective.

He’s on the ground with sake, but on the flip side of production—leading tastings for foreigners, but primarily working at his bar, where he’s serving sake to Japanese people every day.

Brian: Yeah, like you said, this is one thing that, for example, sake, it's kind of natural in a way. It only has these four ingredients: rice, water, koji, and yeast. So, there's no additives, there's no junk, and no preservatives that can oftentimes have you… give you that effect maybe the following day that's not so pleasant.

So, I would say of those four ingredients, the rice type, usually has the biggest impact on flavor. Just similar to wine, where you have grapes that are cultivated just to produce wine, there's rice that's grown just to make sake. And there's about 150 varieties of sake rice. So, these types of rice don't usually… they're not so edible. You can eat it, but it doesn't taste so good. But each rice variety has its own flavor profile.

And that… I would say the rice type has the biggest impact on flavor. As far as aromas go, I think the yeast oftentimes has the biggest impact on the aroma of the sake.

Fermentation & Finishing (18:00)

After the rice is polished—to whatever degree the brewer wants—it’s carefully washed, soaked, and steamed. And then the magic happens. And by magic, I mean that that funny little koji mold is given the opportunity to do its thing.

Sake brewers make something called a shubo, which is a mixture of rice, yeast, and water. You can think of shubo kind of like a sourdough starter…

It’s mixed with more of the same ingredients over several days, and it’s what turns the rice into alcohol. The starches are converted and fermented at the same time, like I said, and we end up with this soupy sort of mash.

At this point, some brewers will add a neutral alcohol to the mash.

- This increases the alcohol content to kill off the remaining yeast and mold,

- It stabilizes the sake so that it doesn’t explode in the bottle later,

- And it improves the final flavor by bringing out more flavor compounds.

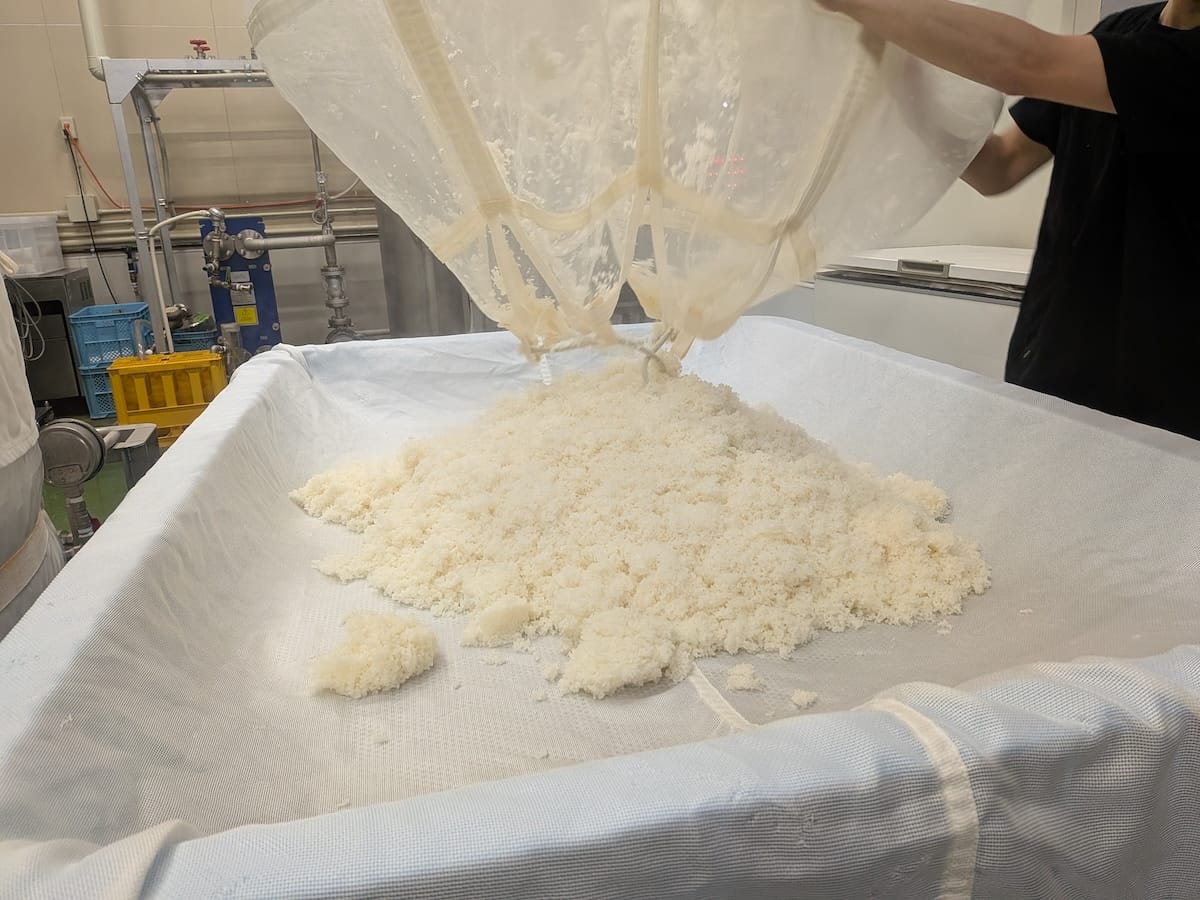

There’s still a lot of solids in the mash at this point, and so the sake has to be pressed to get rid of the solids. The mix is put in cloth bags and then…. well, pressed - usually with a machine or more traditional wooden boxes.

These solids are called lees, and a fun fact: they’re high in antioxidants and amino acids. They can be cooked or pickled, but, when they’re not eaten, they’re often even sold to pharmaceutical companies to be mixed into beauty products.

But I digress….

After those solid lees are removed, the liquid is usually filtered, pasteurized, and left in storage tanks for a few months so that the flavors can integrate and deepen.

Most sake is then diluted with a bit of water and bottled up so it can be delivered to you.

And if this sounds like a lot… that’s because it is!

Miho: So you're becoming an expert.

Caro: You know, I'm going to try. [Both laugh; cheers in Spanish and Japanese]

Yes, I feel like I'm going to do a podcast episode about it, I need to at least know the categories and be able to talk about them.

Miho: Also pronunciation.

Caro: Yes, I have to work on my pronunciation. [Various pronunciation attempts]

Miho: Yes. Genshu. Genshu is a style. So any sake can be Genshu. Exactly. So these two, it's not Genshu, but all of them are Genshu.

Caro: I keep wanting to say Junmai like it's... I keep switching to my Spanish brain and because it's like my brain is like native language, non-native language…

Miho: You speak Spanish?

Caro: Yes, and so I keep wanting to say Hunmai. [More attempts]

I'm going to practice. Next time we meet, I'll have it down...

Sake Categories (20:37)

Let’s dig further into those two big, high-level categories of sake: table sake and premium sake.

Table sake makes up most of the production, and it’s similar to a table wine, or house wine, in that it’s very common at casual restaurants and not even available at higher-end spots.

The rice in table sake can be polished up to 70%, and it’s super affordable. It’s the sake you can easily pick up at a convenience store in Japan, or at an izakaya, their version of a casual gastropub, but it’s probably not the sake you’re getting when you order it outside of Japan.

Premium sake, on the other hand, accounts for about a third of sake production, and it’s the stuff that’s usually exported. Its only ingredients are rice, water, yeast, and koji. So, just those four things.

And this is where it gets complicated because, within premium sake, there are eight categories. I won’t get into all of them here, but they are mostly defined by:

- How much the rice is polished

- If neutral alcohol is added

- And if the brewer has denoted it as special in some way.

Got all that? Great, because there’s a little more. (Laughs)

Challenges/Changes (21:47)

Brian: So, I would say today, you could categorize sake into almost two categories. There's a modern style, and then there's like the classic style. The brewers that are adapted to make these modern-style sake, they're doing quite well. So, they pretty much sell out of all of their product each year. And this modern style of sake appeals to the younger generation of Japanese. It appeals to the foreign market.

I think in Japan, if you were to poll some of these younger Japanese, would think of sake as like an old Japanese man's drink. These classic-style sake, which probably are not so premium to begin with, were kind of like… they had a lot of impact. They were punchy, they were alcoholic.

Whereas, like these more modern style sakes tend to be a little bit more, for lack of a better word, get like a little bit more wine-like. They're floral, and they have some fruit aromas. And they're just a little bit, uh… I guess, they connect more with like the younger generation of Japanese, because the younger generation of Japanese, they've had exposures to craft beers, to cocktails, to wine, whereas like that older generation, like their grandfather's generation, did not.

I previously mentioned that sake became a bona fide industry in the early 1800s. The years that followed were marked by a lot of modernization and improvements… And then came World War II.

Up until this point, all sake was junmai - the “pure” sake that doesn’t have added alcohol. But the war brought rice shortages, and also increased taxes to fund the war.

The government largely took over the production of sake, and they started adding neutral, flavorless alcohol to stretch their limited rice supplies. At the end of the day, this led to a worse product that cost more… and so, predictably, sales plummeted.

In the years that followed, Japanese people developed an affinity for beer, and then other cheap drinks like highballs, and sake’s popularity never really recovered domestically. It’s still drunk, obviously, all the time, but not to the same degree it was before the war. Especially by young people who, to Brian’s point, have been exposed to a lot more variety of drinks.

Brewers have started innovating with more fruity and sparkling varieties of sake… and also embracing the international market for sake, which is growing steadily in places like Europe and North America. Brian estimates that sake exports are up from about 2% when he got started to 7% more recently.

But this hasn’t necessarily translated to more business for brewers.

There are only about 1,500 licensed sake brewers left in Japan, and as few as 1,200 of them are actively making sake.

And if you’re thinking to yourself, well, sounds like there’s room for me to move to Japan and open my own sake brewery [laughs]… not so fast.

The Japanese government doesn’t issue new licenses for sake breweries, in part because they’re already heavily subsidizing production. They really do see sake as the national beverage, and so they want to support it… but not so much that they’re signing up to fund more breweries.

The reality is that the Japanese countryside is shrinking population-wise, and the old school brewers there can’t survive on making table sake - those bottles of non-premium sake with lightly polished rice. They need to make premium sake, send it to the cities at least, and export abroad ideally, in order to make a profit. Which, you know, is easier said than done.

And then there’s the cost of rice…

Rice Prices (25:16)

Yonezawa-san: And sake is at one point, it's a difficult point. We use the ingredients, mainly the rice. Rice is very effort from environment. But now is the summertime in Japan. Too hot.

The rice is no… sometimes is no good quality. But important is the rice quality is…. at a good time, we are making sake very easily. But hard rice is very difficult. But we have a technique, and we find the solution. But maybe this year is the same, is high temperature.

Now is in Japan… rice is a lack of stocks. And now is a big problem. Table rice price is too expensive, go up the price. And normally, a sake rice is under the price of table rice. But now table rice is going up. And this is a big problem for us.

And we, maybe this year, we pay more money. And this meaning is… sake price in the near future is going up.

Caro: Oh, it's going to go up.

Yonezawa-san: This is a problem point.

Rice Shortages (27:08)

That was Yonezawa-san again, the Toji at Akashi, talking about growing challenges in production.

- Rising temperatures have led to rice shortages—and a decrease in quality because higher temperatures can cause cracks and decreased starch content, among other things.

- Japan also has an aging population. There are fewer young people becoming farmers, and thus fewer people growing rice.

- And finally, table rice - AKA the rice we eat — has gotten more expensive due to a whole host of factors I will not get into here. But, suffice to say, that’s causing some farmers to switch from sake rice to table rice, which is not helping.

Serving & Drinking (27:48)

At the end of this last trip to Japan, I was flying out of Tokyo, and so I had to make my way back there before leaving. Instead of staying in Tokyo proper, I decided to spend a week in nearby Yokohama.

Yokohama is technically its own city, right outside of Tokyo… but it’s so close - and so well connected by the bullet train - that it’s basically still Tokyo. I mean, you can get there in under 45 minutes, and I know people whose daily commutes in the US and Mexico are way longer.

So, I got a cheap room for the week, explored the city, took some day trips... and signed up for a sake tasting on a whim.

Now, I’ve done quite a few sake tastings—both in Japan and abroad—and so I didn’t expect this one to be all that different…. Cue me showing up at 1 pm for a tasting and not leaving until 3 am. [Laughs]

This is how I met Brian, and thank god for his little hot plate because I definitely needed some food in my stomach after all that great sake.

Pairing & Serving (28:38)

Brian: Yeah, it's such a versatile beverage. I think a lot of times, as foreigners, we don't think about drinking sake unless we are at a Japanese restaurant or we are having sushi. And, personally, I find that a lot of sake, it's kind of difficult to pair sake with sushi because the ones that have lots of flavor overpower that raw fish.

So, there are a couple of sushi chefs that come to my bar, and I asked them the question, if you had to choose like a category of sake that goes best with sushi, what would it be? Thinking they might say the answer would be like a Daiginjo or Jumai Daiginjo, those premium ones that I mentioned earlier.

They often say it's the Honjozo. And what a Honjozo is, it's kind of the lowest level of the premium category sake. And actually, the Honjozo sake also has some brewer's alcohol added to it. So, this brewer's alcohol is a distilled alcohol. So, it's just a hint that they add and they don't do it to impact the alcohol by volume. They're adding this brewer's alcohol to kind of give out an essence of the sake, or else they're trying to make the body of the sake lighter. That's what it usually does.

So, to drink, to drink a real typical or classic honjozo, you drink it by itself, you're kind of going, hmm, there's not much going on here. It almost has like a… tastes like water, almost, but that's why it works so well like sushi and sashimi.

It enhances those flavors of the sushi, of the raw fish, and it definitely doesn't overpower it. So those… the nice thing about it, they're usually the most inexpensive ones too.

Unlike a lot of alcohols, sake naturally pairs really well with food.

It’s less acidic than wine, so it doesn’t compete with acidic flavors. And, because koji is the ingredient that gives miso paste and soy sauce their umami flavor, it’s great at bringing out those notes in meats, seafood, or cheeses.

But, really, there’s such a variety of sake out there that there’s one to go with just about every dish.

And whether you’re drinking it with food or on its own, it’s generally served the same way—in a small carafe, with tiny cups for each person at your table.

If you want to be a real pro, here are some tips on enjoying sake:

- Never pour for yourself; let your friends do it for you.

- When you do pour, start with your elders or more senior folks if it’s a group from work.

- Hold the sake vessel with both hands—one at the side and one at the bottom.

And, if your sake cup is served to you in a wooden box - that’s called a masu, and it’s very standard for waiters to overpour so that the sake spills into the box. It’s a sign of generosity!

You can drink straight from the box to make sure it doesn’t go to waste.

Serving Temperature (31:18)

Caro: I remember you mentioning a regular who only ever drinks his sake at like a particular warm temperature... That, to me, says there's probably not a right or wrong way. It's probably about personal preference.

Brian: [Laughing] Yeah, unlike wine, there's not any pretentiousness with sake.

Yeah, there's a regular customer, and I don't know if anybody's ever been to Japan during the summer, but it can be very hot and humid. And the last thing you even want to think about is drinking like a hot sake for most people.

But yeah, this guy would drink a hot sake all year round. And he will take sake that are considered to be somewhat taboo to warm up, which, what I mean by that, maybe a Nama sake.

So, namazake are the unpasteurized rice type sake. They're the ones that through. So, when you open a fresh namasake, it almost has the mouth feel of like a sparkly wine. So, it'll have a lot of effervescence. And when you open a new bottle, it's kind of at its peak with that real kind of like lively, bubbly mouth feel. And so he will take, he'll even take those sake and warm it up. But it's a personal preference. [Both laughing] Most people don't usually do that.

Caro: I have and have loved an namazake, and I can't imagine drinking it in a Japanese summer where I can't even think about taking a hot shower, much less drinking a hot beverage. [Laughing]

Brian: But I have to say, though… there's been times where, you know, he's discovered things that nobody ever would have known about, and then he kind of shares it, and so sometimes he's spot on with like some of these new discoveries.

Caro: Yeah, he's doing it for the good of all of us, right? It's like, okay, well, you try everything at that temperature, and then you report back on the ones that work really well at that temperature, and then we'll go there. [laughing]

Brian: Exactly

There are technically ten different temperature ranges you can serve sake at. The idea is that different temperatures bring out different flavors and that, by serving it at the ideal range, you’re going to taste the sake at its best. The care and precision in this has always felt very Japanese to me.

But, for most of us, these temperature ranges really boil down to serving it chilled, at room temp, or heated.

- Chilling is great for sake with intense aromas and flavors. It gives the sake a crisp, refreshing taste, but can also impede the fragrance and dull your tongue from tasting subtle notes if you overchill.

- Room temperature sake is very neutral. You are drinking it at the temperature it was made, and it’s not highlighting or dampening any aromas or flavors.

- And heating sake can enhance the aroma and improve the mouthfeel… and just generally smooth over any rough or bitter notes in a cheaper sake. But it can also overpower more delicate aromas and flavors. This is why, generally, you don’t heat more premium sakes.

But, at the end of the day, it’s all about your personal preference, so try some things and see what you like.

Conclusion (34:22)

This episode really just scratches the tip of the sake category, but hopefully, after listening to me prattle on, you see why it’s such an interesting drink worth diving further into.

So, here are my biggest tips for doing just that…

First, start with Junmai and Daiginjos.

- Junmai means “pure,” as in premium sake without added alcohol. You’ll see the word Junmai (that’s with a J) prominently displayed on the bottle, often combined with other words that denote how much the rice is polished… but focus on the Junmai bit to start.

- Daiginjo is a premium sake with added alcohol. Again, you’ll see it combined with other words, but if it says Diaginjo (with a D as in dog), that means additional alcohol has been added. This isn’t about boosting the ABV, but more about enhancing the aromas and smoothing out the flavors.

Try a handful of both Junmai and Daiginjo sakes to see what differences you notice, and if you prefer one more than the other.

From there, you can dive deeper into the varieties within those categories - different polish rates, different regions, different types of rice, and so on.

Akashi is obviously a brand I love and recommend. Most of their lineup is available across Japan, Europe, and the US, so look for it on menus or online. I’ll put some links in the show notes.

But you can and should also just ask!

Good bottle shops, bars, and restaurants with sake on the menu should be able to not only make recommendations but also help you put your preferences into words.

As a bartender and spirits som, I love when people tell me what they like… but also, my definition of sweet or strong is likely different than yours. And sometimes, when people say sweet, what they really mean is that it reminds them of a sweet thing. So, after you try the bottle, follow up!

Ask, “Is this typical of this style? What would you recommend if I wanted something stronger? Or less sweet? Or if I told you love chardonnay? How would you describe this bottle in terms of categories if I wanted to find something like it?”

I started a note in my phone after my first sake tasting, and I occasionally add to it as I try new things, and it was super helpful for figuring out what I like, but how I can reliably order bottles with a pretty good idea that they’re going to be to my taste.

Super nerd move, I know, but it works!

Conclusion (36:49)

And with that, we’ll call it a wrap on this episode.

You can find the show notes at betweendrinks.co/japanesesake. There are links for Akashi, Brian, and his bar, and a recap of these pro tips. So, you can always just pull it up on your phone next time you want to impress someone with your sake ordering skills.

And if you’re new to Between Drinks, make sure you also sign up for my newsletter while you’re there. It’s where I write about the overlap between travel, culture, and drinks, and it’s basically a mini version of this podcast. So, if you were on it, you would’ve already heard all about Brian and his bar a few months ago after I went. [Laughing]

You can subscribe at that same link: betweendrinks.co/japanesesake

Thanks for listening, and I hope to see you for the next episode as we dive further into other Japanese drinks!

The next one is a good one, and as a little tease, I’ll just say: it’s about the most popular spirit in Japan. Think you know which one that is?

Well, you’ll just have to subscribe and tune in to find out if you’re right!

Show Notes

This episode included interviews with:

- Kimio Yonezawa

President and Toji at Akashi-Tai Brewery - Miho Komatsu

Global Brand Ambassador at Akashi-Tai and WSET Sake Educator - Brian Hutto

Owner of Craft Sake Shoten

Subscribe

Subscribe to the show in your favorite podcast player to make sure you never miss an episode.

And maybe leave a rating/review while you're there? 🙏

Sake Ordering Cheatsheet

| No added alcohol | With added alcohol | |

| 30% polish | Junmai | Honjozo |

| 40% polish | Junmai Ginjo | Ginjo |

| 50% polish | Junmai Daiginjo | Daiginjo |

- Consider trying both Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo sake to start.

- If you like bold, vibrant flavors, try a Namasaki. This is an unpasteurized sake that's often fizzy. It requires refrigeration and has a shorter shelf life.

- Honjozo is generally seen as less premium because of it's polish rate, but it can be cheaper and great for pairing with food.

I've spent +6 months traveling the country, visiting dozens of cities, and collecting hella Google Maps pins. Get all my recs here!