Mexican Coffee

Did you think we were done with Mexican drinks? Never!

Popping in this week to share a bonus episode about one of the world’s most popular (and maligned) beverages.

Mexican coffee doesn’t always get its due, and so I set out to find out why.

Why are coffee lovers so surprised to find good Mexican coffee when they come to visit? And why don’t you ever see it at your local cafe?

Mexican Coffee

Coffee is the most popular beverage in the world, after water… and it can feel almost as necessary. And yet, most of us don’t know much about what goes into making our morning ritual happen.

Enter me, your nerdy drink-loving friend!

I talked to three coffee expert friends here in Mexico to understand:

- What people mean when they say “specialty coffee”

- The interesting history that brought coffee to Mexico—and the revolution that put coffee growing in the hands of indigenous peoples

- Why Mexican coffee doesn’t always get its due internationally

- How to support producers (and ethical brands) by asking the right questions before you buy your next coffee

- The random reason Mexico is associated with decaf coffee abroad

Subscribe

Subscribe to the show in your favorite podcast player to make sure you never miss an episode!

© Between Drinks 2025

More from this episode

Transcript

Show Intro (00:00)

Welcome to Between Drinks, a podcast where we travel the world one drink at a time.

I’m your host, Caro Griffin, a mezcal sommelier, traveling bartender, and all-around drinks nerd.

In each episode, I’ll take you somewhere new to dive into a local drink with a story to tell. We’ll talk about its history and how it’s made, but also its connection to the place and the people that make it what it is.

There’s a great story behind every great drink, and I can’t wait to share them with you.

Episode Intro (00:30)

Vera: Coffee is not a cheap product.

I, you know, I think… Ben Affleck, in his years, was a gorgeous man, but I saw his commercial on Dunkin' Donuts for $1 coffee.. I was like, shocked, I was mortified. Like, no, I can’t support this dude anymore.

Caro: [Laughing] You were like, he's no longer on my list.

Vera: No, no, I don't need that.

Because I think we have to value the work, the people who are doing this, the challenges they face. So, if your cup of coffee becomes slightly more expensive, it's because there's a reason.

One, I think we haven't paid them enough for the last 50 years.

Secondly, we have to now do better. And maybe… I would not recommend drinking less. I would recommend making smarter decisions on where you're drinking your coffee.

-

That was my friend Vera Espindola Rafael. She’s a Development Economist who works with coffee supply chains to make them more inclusive, ethical, sustainable… all the good stuff.

I don’t consider myself a coffee person, per se, but I am surrounded by coffee people like Vera. They’re not all as knowledgeable about coffee as her, because almost no one is… but their cumulative good taste, and six years in Mexico, have taught me a lot.

They’ve turned me from someone who only drank dirty chai lattes into someone who…. Well, mostly still orders a basic iced latte, but can no longer stomach them from just anywhere.

So, why are we talking about my coffee preferences on a podcast about booze?

Because Between Drinks is about drinks, first and foremost.

Sometimes those are fermented drinks like beer and wine, and usually they’re spirits like whiskey and rum… but a drink doesn’t have to have alcohol to be widely influential, or tell us about a place.

I learned this firsthand during my nomad phase, when I spent years working remotely from coffee shops around the world.

It made me realize that there are:

- Countries that drink coffee,

- Countries that have a coffee culture where people drink it at cafes, and care about the quality or preparation,

- and even fewer still with a good cafe culture.

Cafes are to coffee what bars are to booze.

They are the meeting point where consumers are introduced to new coffees, and can learn more about what they like, and how it’s made. You don’t learn that from the coffee aisle of a grocery store, just like you don’t learn about spirits in the aisle of a liquor store.

You learn about spirits in a bar, and you learn about coffee in a cafe.

Mexico is one of the few places that has both great coffee and a great cafe culture.

Mexico City, in particular, has the best cafe culture I’ve ever seen. The quality of the coffee, the vibes of the cafes, the baristas who know what they’re doing… It’s unmatched. And a day rarely goes by that I don’t step into a cafe.

So, between my own preferences, the increased tourism here, and the coffee lovers in my life who’ve come to visit from countries all over the world… I’ve noticed that Mexican coffee always comes as a bit of a surprise to foreigners and even to locals.

Which is unfortunate… because Mexico does have coffee, great coffee, but it’s not well-known around the world. And I wanted to understand why.

History of Coffee (03:40)

Vera: So, I studied development economics. And the reason why I started to study this because, in part, both of my families, farming families, mostly subsistence farming. And I was always triggered by the level of richness all these campos, all these fields have. And what triggered me most is that… for some reason… the countries and the people that were living within these beautiful landscapes, including my family, were never really well off. They were always struggling.

And I had the opportunity to enter this program, which I did, and I think my main objective was to try to understand the context… I love numbers, the microeconomic context on what is needed to change this… is it, you know… what kind of elements need to be changed?

-

Coffee comes from a type of stone fruit, or cherry, which is native to Africa and Asia.

What we call coffee beans are actually the roasted seeds from this fruit.

Ethiopia is widely considered to be the birthplace of the plant. But the drink, as we know it today, first became popular in Yemen in the fifteenth century. It traveled through the Arab world, where it was embraced as an alternative to alcohol.

And, from there, coffee spread to Europe through the Ottoman Empire’s trade routes… and it went on to quite literally change the world.

-

Coffee didn’t make it to Mexico until later, when Spanish colonizers brought it to the Americas in the late 1700s. And it was longer still before it became a popular crop.

You see, drinks like chocolate and atole were rooted in Mexican culture, and so coffee cultivation didn’t initially take off. It took years for coffee plantations to crop up in southern Mexico. And it took even longer for Mexicans to actually start drinking coffee.

The thing that changed the tides was the Mexican Revolution—a long civil war that ended in 1917 with an overthrown dictator and a new constitution.

It brought on land reforms that redistributed large estates into smaller plots of land, many of which went to Indigenous peoples and rural workers who had previously been indentured to large coffee plantations. They used their knowledge to start their own small coffee farms on this land.

And, in 1958, the government founded a national coffee institute to (1) give these farmers much-needed support and (2) help establish Mexico as a coffee-producing country in the global market.

At first, this worked. Rural areas saw a 900% increase in coffee production! In just twenty years!

So… what happened? Why isn’t Mexico this big, known deal in the world of international coffee?

Intro to Mexican Coffee (06:40)

Most coffee producers are located in what’s called the "Bean Belt," a region around the equator that includes parts of Central America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

In Mexico, most coffee comes from four southern states - which makes sense because, you know, that’s where the equator is…

- We’ve got Chiapas, a southern state that borders Guatemala, as the biggest producer. This is where a lot of those original plantations were, and so it's where a lot of land was handed over to those small producers originally.

- Veracruz, northwest of that, is where coffee was first introduced in Mexico, and they’re still a big producer today.

- Their neighbor, Puebla, is a newer coffee state known for its unique microclimates.

- And then there’s Oaxaca, which is known for its small, traditional production.

But, really… all Mexican coffee comes from small, traditional production and small producers.

No one’s counted them since 2017, but it’s estimated that we have around 500,000 coffee producers.

The vast majority are Indigenous. They’re farming small plots of land no bigger than 3 hectares, or about 7 and a half acres. And they’re all pretty much growing the same beans and processing them the same way.

And yet, despite those similarities, there’s a lot of variety in the flavor profiles themselves.

Production / Flavor Profiles (08:00)

Vera: I think what is a shame is that we have unfortunately not put that more on paper as a country. But even in a region or a state like Oaxaca, has around five regions that produce coffee. And within those regions, you have a different type of profile.

I think that that's a work that still needs to be uncovered, put more on paper, because if you talk to the cuppers, they would say, “No, oh, this is definitely a Chiapas one. I think this is more from Los Altos, you know…”

There are some efforts being done. For example, think Veracruz has done a work through the Institute of Café. They've done quite some work in order to give every region within Veracruz a cupping profile.

There's a similar kind of work being done for Los Altos de Chapas that… within the Altos de Chapas, they are trying to give that a specific profile because they're different type of microclimates. The flavor profile of coffee is like wine, mainly because of the terroir they're in, and the variety that they have.

So, if you have different varieties, then you already have a different flavor profile. It does depend on those types of externalities.

-

Simply put, growing coffee in different environments produces different flavor profiles.

And then there’s the bean itself, and the way it’s grown and harvested.

In Mexico, we almost exclusively grow arabica coffee, and 90% of it undergoes “wet processing.”

Here’s an overview of how it all works, from seed to bean:

- Coffee plants start as seeds. It takes 3-4 years from planting to first harvest. And, after the first year, it takes about ~9 months for the coffee cherries to mature.

- The plants have to be weeded, pruned, and protected from pests during this time, so it’s definitely not a hands-off process.

- When the plants are ready, the berries are harvested by hand. You only want bright red, perfectly ripe berries, and so farmers will make several passes of the same field to pick each one at the right time.

- After harvesting, berries are sorted to remove any unripe or damaged berries that snuck in.

- The skin and pulp are removed, leaving the mucilage-covered green bean.

- The beans are fermented in tanks, and then thoroughly rinsed to remove the rest of the mucilage.

- Afterwards, the beans are spread out on drying beds to, well, dry.

- And then finally, the outer parchment layer around the bean is removed.

All that’s left is the green coffee bean, and it’s these that are packed for sale and eventually roasted by coffee roasters around the world.

Washed coffees like these—where the mucilage is removed before drying—tend to have cleaner, brighter, and more acidic flavor profiles.

But, in general, I’d say the notes in Mexican coffee lean more nutty and chocolatey. There are sometimes floral notes or notes of citrus, depending on the region, but it’s not common to find big, fruity flavors that you can find in coffee from some other countries.

Mexican coffee has got its own profile, really defined by those nutty, chocolatey notes.

Challenges in Producing (10:50)

Vera: Small holders, in that sense, and particularly the ones in coffee, often are dependent on that crop. It's, for them, a cash crop; it's, for them, what they know how to do.

So, it's very hard to detach yourself from that when you already have that, you know, plot of land. You have planted your trees. This is what you know from your dad, mom, or even grandparents. This is what we do.

There's a sense of identity that's sometimes hard to explain to other producers who produce different types of things. For example, if you say to a producer of lettuce, “Please switch to pepino, to cucumber,” then well… “Ah, fine, you know, whatever the market wants.”

There's a different level of attachment, right? And then in a country like Mexico, we have around 70% of all our producers are indigenous communities. So that gives you a different layer of, um, I don't wanna use the word complexity, I would just say there’s a challenge in that.

These are often also in areas that are quite remote. It’s not necessarily where all the conditions are in place to make life easy. Lack of infrastructure is also not helping. And then of course we also have the part that the indigenous communities, where they are also in, some of them mainly also speak their own language.

Now, why is that perhaps a challenge? Because a lot of the educational material that's out there and presented is mostly not even in Spanish, let alone in an indigenous language.

So, when you sum up these challenges, and I will then focus on one in particular that we have lived with for the last I would say 40-50 years in a market where coffee prices have been low. That means that you know, these producers are often living in poor conditions.

And this is not me stating an opinion. This isfundmentado by an ICO report that, if you compare countries that produce coffee, with countries that don't produce coffee, the ones that produce coffee are more likely to be in poverty than the ones that don't produce coffee.

And this is tremendously sad because coffee, as a beverage, is the beverage which we, in theory, can live without… but we don't want to as a society.

-

The global coffee industry is estimated to be worth more than $200 billion USD, but only 10% of the generated wealth stays in the coffee-producing countries.

And that’s because the vast majority of coffee is exported. And it’s exported in a really complex supply chain, and so most of the profit is made by middlemen, roasters, and retailers.

In a world where inflation is rampant and it feels like everything is getting more expensive, coffee prices - or, at least, the ones producers are paid for their green beans - have actually dropped.

At the same time, the countries that produce coffee have more challenges than ever—political instability, climate change, and its related migration… and then there are the pests, diseases, and soil fertility.

I could go on, but the gist is that coffee has a rough road ahead everywhere, and Mexico is no different.

So, what are we to do?

Well, there are some better choices we can make as consumers, for sure, and we’ll talk about those… but there’s also some good news at the macro level.

Vera actually did a big study recently about how coffee-producing countries can support their producers by building up demand at home.

And it boils down to this:

- The reason coffee is almost always exported from where it’s grown is that’s how producers used to get the best price.

- But now that those prices are dropping, domestic markets are more competitive.

- And when you sell in your own country, there are fewer middlemen, less taxes, duties, and so on.

- So, now producers in countries like Mexico are finding that they can actually get a better rate by selling their coffee to local buyers.

- So, cultivating a specialty coffee scene in coffee-producing countries—with cafes that sell their coffee, and consumers who are eager to buy it—is a great way to grow the domestic market and get more money in those farmers’ pockets.

This has been a relatively recent change, but it’s surely one of the reasons that Mexican coffee isn’t being shipped abroad as often… and I can’t be mad about that when I understand this reasoning.

Also, I may not work in coffee… but trust me when I say that me and my coffee budget… we’re doing our part down here in CDMX to build up that local demand.

Types of Coffee (15:14)

Now that we know how coffee is grown and harvested, let’s talk about what happens to those little green beans after they’re roasted.

Coffee is a huge industry, and there are a bunch of different categories.

The majority of the coffee that’s produced is what we’ll call “conventional coffee,” or “commodity coffee.”

You know, the big brands like Folger’s that make the stuff you see in the supermarket.

This kind of coffee accounts for about 60% of the market, followed by instant coffee or “soluble” coffee, which is another 15-20%.

These coffees are usually a blend of different types, from different regions, and so you usually don’t see any information on the package about where the beans are from.

On the flip side, high-quality coffee is usually referred to as “specialty coffee.”

Specialty coffee has a high rating on what’s called the Q-Scale, which we’ll talk more about in a bit.

It’s what you buy directly from a local roaster, or at a cafe where you can clearly see details like country of origin, the type of bean, and the flavor notes. And these coffees account for about 10-15% of the market.

-

Caro: So, can I ask what grade is the coffee? Is that a faux pas to ask? I don't know what… I mean, I know there's the scale, and I'm like somewhat familiar with it. But like obviously 96 or 99… that's like almost impossible.

Mau: This is a very funny question because, quite a few years ago, having 100 points coffee, which is like the top, was essentially technically impossible. Until this Panama coffee came by and was the Nadia Comaneci of the coffee. [Laughs] And they had to remake the whole grading around the coffee.

Caro: They were like, “Hold my beer, I mean coffee.”

Mau: Exactly. Like they were like uh no, we have to, you know, like raise our standards in order to not surpass the 100 points.

We actually had one of those. It was a crazy Geisha 90-plus back in 2018, I think. And it was 98 points. So it's like the 1% of the 1% of the 1% of coffee.

Caro: Served at your neighborhood cafe in Roma Norte. [Both laughing]

Mau: Trust me, it spoiled everybody. It was like having generous wine or having an oporto… If you close your eyes and somebody tells you it is not coffee, you might be like, “Oh, what is this?” Like, this is not coffee. What is so different?

Caro: It transcends coffee to another level.

Mau: Exactly.

-

That was my Mauricio Zubirats, or Mau. He’s a chef and owner of one of my favorite cafes in Mexico City, Raku Cafe.

Raku is a Japanese-inspired cafe, but they proudly serve Mexican specialty coffee.

Specialty coffee is any coffee that scores 80 or above on a grading system developed by the Specialty Coffee Association. They certify experts called Q-Graders to evaluate coffee with a process called cupping.

Anything below 80 is considered commercial-grade and sold for those commercial or commodity coffees we just talked about.

Now, Mau is a coffee snob of the highest degree. [Laughs]

He spends an inordinate amount of time cupping his coffee and fine-tuning his espresso machine… and it’s made Raku well-known for having really great, Mexican coffee, specifically.

Which is a little ironic, because he didn’t originally serve coffee from Mexico!

-

Mau: We were serving international beans at the time, and we were maybe one of a few specialty coffee shops in Mexico City that actually sold international, roasted-abroad coffees, in Mexico City.

Then this amazing coffee roaster came by, and he was like, you know, we can definitely do something great with Mexican beans. And he opened my eyes towards, you know, like all the incredible, insane specialty coffee that you can get in Mexico.

Like they're going to be obviously very different from what you can get from… Ethiopia or Panama or whatever, but they're also incredible in Mexico.

-

This, in a sense, is what started me down this rabbit hole into Mexican coffee.

Mexican coffee can be great. It has unique flavor profiles, about half of it is considered specialty coffee quality, and yet… even people who love coffee have never really heard of it.

So, again, why is that?

-

Vera: Specialty coffee’s movement started in the 90s, you know, and the specialty coffee movement itself has been through different phases where… when we started to understand really where coffee was from, I have to say… I was already working in coffee. And then people started to ask, so which country, which region is it? This is 2010.

So it's not that… we are talking like a bottle of wine, which has a different history in understanding that we want to know where it's from.

That movement of coffee, of that third wave, is very recent. So, when we're starting to uncover other countries that produce this, and Mexico being one of them, I would say other countries with their infrastructure… they started to invest a little bit more than we did.

I think that Mexico would say, in the last eight years, has started to focus more on producing differentiated coffee, specialty coffee, understanding that that potential was there. And there've been different initiatives that helped us as consumers, and part of the sector, understand that basically we do have great quality coffee.

It's simply a matter of wanting and creating a market for it. And one of the great and cool things that happened very organically is that the Mexican consumer itself started to ask for it more. And I think that has helped and shaped the consumption of specialty coffee in Mexico.

-

You know how I told you that Mexico started a national coffee institute to support farmers and grow Mexican coffee’s reputation abroad?

Well, they shut that institute down in 1989. The government made a bunch of economic reforms, so it was a casualty of those. And, unfortunately, that was around the time that third-wave coffee exploded.

Third-wave coffee emphasizes single-origin coffees, lighter roasting, and artisanal brewing methods. It was the first time that coffee, at scale, was treated as a craft product similar to wine or craft beer. It was when a lot of people first started to pay attention to where their coffee came from, and Mexican producers didn’t get to fully capitalize on that.

Was that entirely because the Institute closed?

No, but it was one factor.

Some of the others are: Mexican producers are very small. They’re less “productive” when you look at how much they produce per hectare. They’re more isolated, and so they don’t have the support or resources that producers in some more established countries do.

And, now, in recent years, an increasing amount of Mexican coffee is staying in Mexico because that’s where producers can get a better price… and, we talked about this… that can actually be a good thing in a lot of ways.

But there is one area where Mexico does come up a lot in the coffee conversation abroad…

Decaf Coffee (22:15)

Mau: I don't know why there are not many like, super high-quality coffee beans in different places.

For example, we just went to Japan, as you said, and I took Raku coffee to different places, like some of the best coffee shops in the world, maybe, with incredible baristas who are like… world champion barista of like whatever. Like they're insanely professional and they've tasted coffees from all over the world.

And they're… every time that I had the same answer. It was like, “Oh, so we thought that Mexico only had decaf.”

That is kind of like infuriating, and at the same time, it's kind of exhausting. And it is like, oh, decaf. I'm like, “Nooo… I don't ever drink decaf.”

Caro: Never.

Mau: But people in Japan, for example, they always think that Mexico only has decaf to offer.

-

So, this is a little bit of an aside, but I want to talk about decaffeinated coffee for a quick sec.

Decaf coffee is a pretty niche market… and I’m not in that market. So, I never gave decaf much thought until I started drinking specialty coffee in Mexico and then started talking about it abroad.

I’d wander into a specialty coffee shop in say, Europe or Japan, and very rarely, I’d see a Mexican coffee and comment on it. Or, more commonly, I’d get into a conversation about coffee with a barista, and when I mentioned Mexican coffee, I’d get something like:

“You mean decaf?”

It was all very perplexing.

Especially because, when I brought it up to coffee-loving friends in Mexico, some of them had had similar experiences… but also couldn’t explain why Mexico seems to be associated with decaf abroad.

And then I talked to Vera about it…

-

Vera: We have one of the biggest decaf plants in the world, in Córdoba.

I think, in the world there are like five to ten. And one of the biggest ones, are here in Mexico, in Córdoba.

I mean, yeah, there are two patented methods. One of them is owned by this Mexican family. So, a lot of the coffee from Africa, once the mountain water is processed, they are exported to Mexico.

It's brought into Cordoba, it's decaffeinated, and then sent back to either Germany or whatever European country they drink their decaf coffee in.

-

And, suddenly, it all made sense.

Brewing Coffee (24:40)

Vera: There are a lot of people that love to talk about the how you prepare certain coffee, which has to do with the bean size, the bean density. So… another rabbit hole, as you just said, yeah.

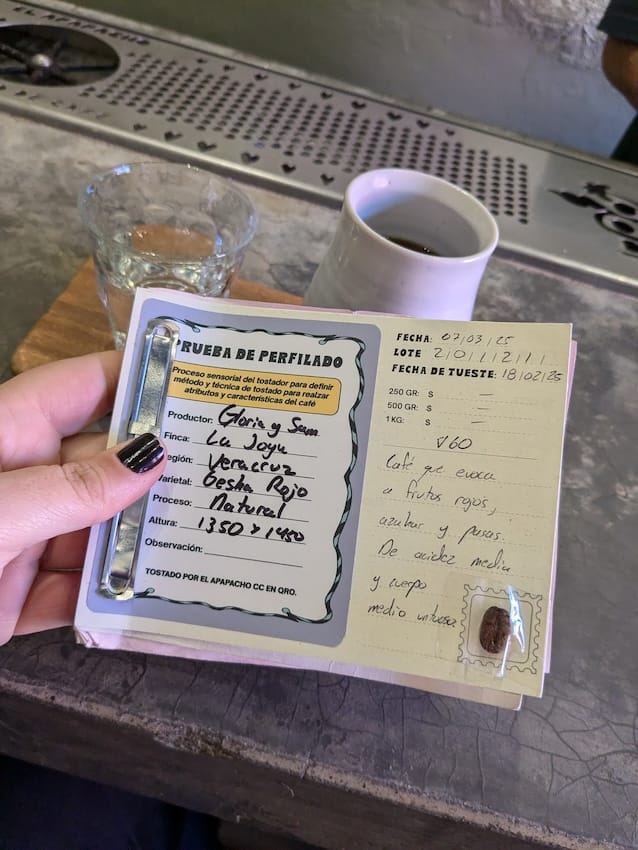

Caro: Absolutely. Rhi and I went to Queretaro last week, and… we went to El Apapacho.

Oh my God, that coffee… bar is made in a government laboratory for people like Rhi. She was in heaven, and when she ordered a bag to go, they even pulled out a little, like, pre-printed card, and they wrote down all the brewing instructions. They were like, “Okay, you use a Chemex. Do you hand grind? Like what's your… You need 30 rotations.” And it was like… I'd never seen anyone give the card with the bag. And I was like, this was amazing.

Even when they served my geisha variety, it was like they had like a little printed card and the bean was taped to it, had all the details. And I was like, I wish every beverage came with this level of detail and context so that we could really appreciate everything that goes into it.

Vera: Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. I actually really enjoy that because I do think it's part of understanding that coffee is not just coffee. It has multiple layers, and it's beautiful.

-

That was Vera and me geeking out about a cafe in Querétaro called Apapacho, and Rhi is the one who really got me into coffee in the first place.

She used to work in specialty coffee and, when we moved in together, the smell of beautiful coffee just started wafting up the stairs at predictable intervals.

And, thanks to her, I do know how brewing works on a theoretical level so let’s go through it…

- A cup of coffee is about 98% water, and the rest is Total Dissolved Solids, or TDS.

- The more TDS, the stronger your brewed coffee.

- The longer the coffee and water are in contact, the more coffee compounds are extracted.

- And a finer grind increases surface area, which causes extraction to happen faster.

- Other factors like water quality and temperature, type of filter, and brew method also play a role.

- And the brew method could be a Chemx, a V60, a standard countertop coffee maker, or seemingly a million other things. I feel like I’m constantly discovering new ones.

Rhi literally wrote a book on the subject, so I’ll link to it in the show notes for anyone interested in going down this whole rabbit hole of brewing… because it is a rabbit hole, but also a pretty special one.

-

Rhi: I’m passionate about beverages in general, but what makes coffee my absolute favorite, and Mexican coffee in particular, is that coffee is equal, I think, in complexity to wine or a spirit, or something like that… but then there is this whole side and stage of influence the barista or consumer has over it.

You can’t just pour coffee out of a bottle. There are hundreds of little decisions you can make to tailor a coffee to your preferences. It’s a beautiful collaboration between the bean and the drinker that I think really honors the work of the people who labored to get it to you.

That is a thousand percent part of the reason I’m totally fine taking thirty minutes in the morning to make my own coffee. Not for everybody, but if you know you know... and if you get it, you get it.

-

Cafes & Baristas (28:08)

That was Rhi herself, highlighting something that’s really unique about coffee. And that’s the “collaboration,” as she calls it.

There’s no other beverage that works this way. Even the best, most artisanal beer, wine, or spirits… they come out of a bottle as they are.

But good coffee isn’t poured out of a bottle. It’s brewed—by you, or by your friendly neighborhood barista.

-

Mau: Our espresso, if I'm not wrong, this year was like 89 points, which is not extremely high, but it is really good for having a daily coffee. And uh, it is an anaerobic fermentation process.

So, with the right equipment and the right knowledge, you're able to take out way more from a coffee than you would do with a regular espresso machine, for example, or without all the daily experimentation that we've been through over these six years with the machine that we have now.

We started with a Miselco GS3, which is like the starting kit for every specialty coffee shop in the world, maybe. And we changed into Slayer Steam LP, which is an American machine based in Seattle.

They changed our coffee game forever. Like, the espresso game was a totally different one because you have a lot of different variables that you can control. And you can play with pre-infusion, post-infusion, extraction, temperature, and so…, and even with an 89 points, you can get an incredible espresso that you might not be able to get with a 90-something on a regular machine.

-

Baristas and cafes play an important role in coffee because of the control they have over your coffee. The right brew method, the right barista, the right adjustments to your espresso machine… they can take a good coffee and make it great.

And Mexican baristas, in particular, I feel like know what they’re doing. It’s one of the many reasons why I love the cafe culture here.

But there are good cafes around the world. Maybe not quite as many as we have (ha)… but good cafes, serving good coffee, that’s brewed well.

But how do you take it a step further than that?

How do you choose the right beans when there are multiple types on offer?

And how do you know if your coffee is coming from an ethical source that pays producers what they deserve?

What Consumers Can Do (30:20)

Vera: If it's not explained to you, when you order it at a cafe, explain where… Well, it's from Honduras. Which part of Honduras? You know, ask that question.

Is it from a co-op? Is it not from a co-op? Okay.

It doesn't necessarily define that they were paid fairly. It does give you an indication of how that supply chain is working. Because I have been in a situation where I ask those questions… “Well, Honduras, I don’t know, north, south…” and they just want to continue with their lives.

Then you don't care.

Do I want to continue here for the vibe? Maybe. But I, as a consumer, do care where the coffee comes from. Maybe I will go somewhere else, but they do give me that, you know, explanation of where a specific coffee comes from.

So, for example, if you ask me, Vera, I'm going to Chicago next week, do you know a roaster that cares?

Yes, for example, Metric Coffee cares. Metric coffee has sat with me and done the numbers and said, “Vera, so what if we give more to the producer and you get less as an exporter?”

Those are the rosters that you want to drink coffee from. And I would say, yes, it's a little bit of asking, but even their staff would know because it's a roaster that puts it in their staff [laughs] in their education and formation.

So, ask where it's from, and how are you paying the producers? Or, how are you assuring that the producers are paid better? Ask there. And I think that those are easy questions and maybe sparks a different conversation, and maybe they don't know, but they're also eager to find out for you. Who knows?

-

It’s funny because every time I talk to a coffee person about supporting good producers and buying ethically made coffee…. [beat] They give me the same answer I give people about mezcal.

For those of you who don’t know, I’m a mezcal sommelier and I have lots of feelings about it.

People ask me for bottle recommendations all the time, and I think they are just expecting me to rattle off some brands. Which I can do… but it’s also less straightforward than that.

Because it’s an artisanal product with limited quantities, you can’t buy the same bottles everywhere. You have to ask questions. And, even if you don’t know the… quote-unquote “right answers,” the fact that the answers are clearly printed on the bottle, or readily available from the person selling it to you… Well, that’s a good sign. It means you’re on the right track.

And coffee works the same way.

The fact that a bag of coffee beans has detailed information about where it’s from, how it was made, and what the flavor notes are… does not automatically mean it’s an ethically made coffee, or even a good coffee. But it means you’re on the right track.

So, if you’re at a coffee shop selling specialty coffee, ask the questions.

If they’re offering a line-up of single-origin coffees and selling bags of their coffee at a premium, they should be able to answer basic questions about where it’s from and who’s making it.

And, as long as you’re not asking during a big rush, they should even be excited to tell you!

But if they’re not… that’s a sign.

Maybe you order anyway. You have a meeting to get to, or you’re meeting a friend there. Maybe you need a quick cup of caffeine the next time you’re at an airport and you get that $1 Ben Affleck-endorsed coffee from Dunkin’ Donuts. We’ve all done it! (Except maybe Rhi and Vera but I definitely have so I hear you…)

The answer is rarely perfection, but effort.

Make the effort to learn a little more about what you’re drinking, and make decisions accordingly. Maybe that means you stop going through the drive-thru altogether, or maybe it just means making sure a few more of the cups you drink each week come from better sources.

Most of us are creatures of habit, so even doing the research once can have a big impact. Check out the cafes and roasters near you, verify that they’re worth your support, and then… just keep supporting them.

Those people in the fields, who handpick every single berry that’s going to turn into your morning coffee… they deserve that much, right?

And that’s really what I hope you take away from this whole season on Mexican drinks. A little bit of effort from a lot of people can make a big impact.

And, as a bonus, that effort will pay off in the form of some really good drinks.

Conclusion (34:28)

Well, that’s all for this season, folks.

Mexico’s home, so I’m sure we’ll be back soon enough. There are so many more beverages I could dive into! But I’m also excited for the next season, which will be about…. drum roll…. JAPAN!

I’ve spent almost six months exploring Japan over the last few years, and recently got back from yet another trip where I dove into a few of the many great drinks being made there.

Those delicious bevvys will be the focus of the next season. And it will be coming to a podcast player near you super soon!

In the meantime, make sure you’re subscribed to my newsletter.

I write about the overlap between travel, culture, and drinks. It’s where I share a lot of the behind-the-scenes stuff that goes into making these eps, as well as just general travel stories and recommendations for your next trip.

You can subscribe at betweendrinks.co/mexicancoffee. You’ll also find there the show notes, transcript, and some additional recs for Mexican coffee and where to look for it in the US and abroad.

Thanks for listening, and I hope to see you on our virtual trip to Japan next season!

Show Notes

Interviews:

Mentioned:

- Raku Cafe (CDMX)

- El Apapacho (Querétaro)

- Metric Coffee (Chicago)

- The e-book Rhi wrote

Where to Buy Mexican Coffee

Mexico

Most specialty coffee shops serve local coffee. Just ask!

Here are some of my favorites:

CDMX —

- Raku (Roma Norte)

- Barra de Cafe Casa Malinche (Coyoacán)

- Blend Station (Condesa, Roma, Polanco)

- Brown Caffeine Lab (Roma Sur)

- Buna (Doctores, Condesa, Roma)

- Café Avellaneda (Coyoacán)

- Fuego y Café (Condesa)

- Qūentin Café (Condesa, Roma)

Querétaro —

Online —

- Many of the cafes above will ship domestically. Just check their websites!

- Ratiorama also offers a coffee subscription with great local coffee, including some of the roasters above.

United States

Your best bet is to just ask at your local cafe! (If you're not sure where to start, do a Google Maps search for "specialty coffee" near you.)

Many roasters will also ship their coffee to you. The ones below currently stock great Mexican beans:

- Colectivo Coffee (Chicago, Madison, Milwaukee)

- Killer Coffee Beans (South Florida)

- Lima Coffee Roasters (Fort Collins)

- Metric Coffee (Chicago)

- Ruta Maya (Texas)